By Paulo Camacho

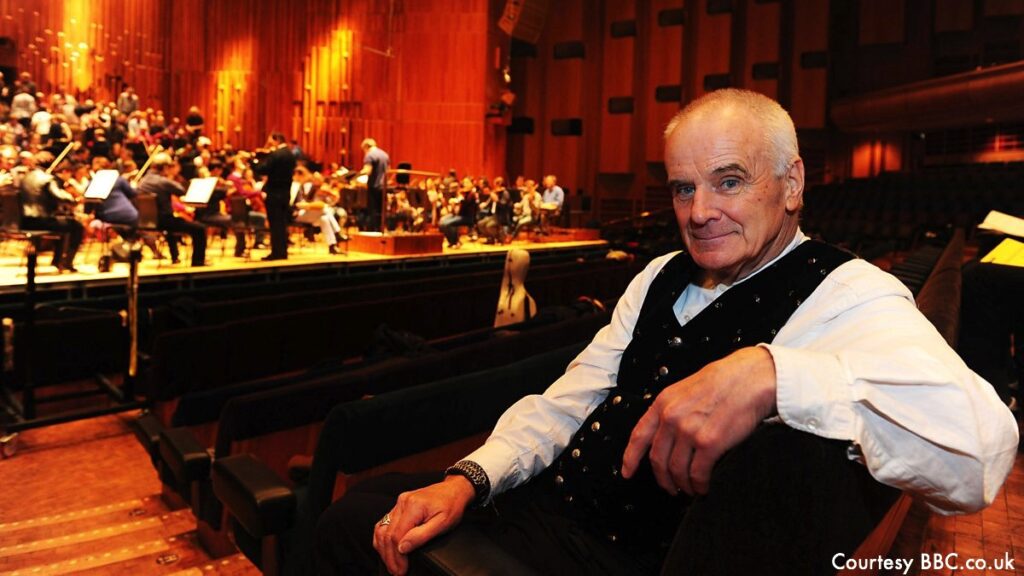

Renowned British composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Master of the Queen’s Music, passed away at 81.

On March 14, the classical music world lost one of its greatest British sons.

Composer Peter Maxwell Davies lost his battle with leukemia last Monday, at the age of 81. While he may not have been universally known in the mainstream, Davies was beloved in his native country, and is universally acknowledged as one of the foremost contemporary composers of the 20th century.

He was the associate composer and conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, and was the Composer Laureate for the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. He also received a number of honors in his storied career, including an honorary doctorate of music from Oxford University in 2005, a knighthood in 1987, and the prestigious appointment as Master of the Queen’s Music in 2004.

Born to a modest household in Lancashire in 1934, to Thomas and Hilda Davies, Peter knew from an early age that he would grow up to be a composer. At the age of four, Davies’ parents took him to a performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Gondoliers, and he was enamored with the idea of composing music.

He soon found himself with a great aptitude for music. Once upon a time, however, he was almost derailed from his burgeoning musical aspirations: his headmaster at Leigh Boy’s Grammar School forbade him from taking A-Level music courses. Despite the discouragement, Davies took the entrance exams privately, forcing the headmaster’s hand when he dazzled examiners with his abilities.

At the age of fourteen, his avant-garde roots would begin to materialize — he submitted a piece called “Blue Ice” to the BBC radio show Children’s Hour, and the show’s producer decided to show the piece to its resident singer, Violet Carson. Her assessment?

“He’s either quite brilliant, or quite mad.”

It would be this distinction early in his career, coupled with the many of his over 300 career works following the same noisy and chaotic themes, that would earn him the reputation of being an enfant terrible in the scope of contemporary classical music. It was reflected in works like Eight Songs for a Mad King, which premiered in April 1969. The screeching melodies and chaotic arrangements made for an audible portrait of a truly insane ruler.

Ironically, the most well-known piece of his vast repertoire was unlike most of the work that made him known, historically in the music world. In his seminal work, Farewell to Stromness, was a piano interlude from The Yellow Cake Revue. The entire piece was written as a response to the reports that halted plans for uranium mining to begin in the Scottish town of Stromness, on the island of Orkney, Scotland — a place he would reside in the latter half of his life.

The interlude, itself, evokes images that harken back to simpler times — a time where the modernization and industrialization of uranium mining were not present. Its minor-to-major-to-minor melodies speak to the potential tragedy that would have befallen the simple town of Stromness — a poetic loss of innocence, to be sure.

It was stories like this that helped define the latter part of his life’s work. He became a staunch environmentalist soon after he wrote Farewell to Stromness, and he focused much of his later work on the themes of environmental responsibility, war and politics.

Davies will be remembered for the eclectic styles of music he produced and cultivated early in life, his sense of character in the face of social issues, and, above all, his never-ending drive to make music. It was, unironically, the reason he lived for as long as he did, and it expanded his thinking as he got later in life. In the years before his death, he compared the very nature of being to the core understanding of music, itself:

Nature doesn’t concern itself with meaning: it just is. And it has been a huge joy and great privilege to have in some way tapped into that energy. […] I think in any composer worth their salt, you feel that come through the music — you feel something that is absolutely transcendental.