By Paulo Camacho

He was a man of the people, and represented so much to so many. He was a world-class talker, an advocate for social justice, and — to many in the sports world — he was quite possibly the greatest athlete who ever lived. He was an influence in many facets of life, far beyond the boxing ring: politics, race relations, and — believe it or not — even the world of music.

Despite brashly making his mark in a turbulent period of American history, the world would proudly chant his name:

Ali.

On June 3rd, legendary athlete and public figure Muhammad Ali, formerly known as Cassius Clay, passed away from complications related to sepsis. He was 74 years old. Throughout his life, he was regarded just as much for his unrepentant, brash rhetoric off of the squared circle, as his unmatched pugilistic prowess on it.

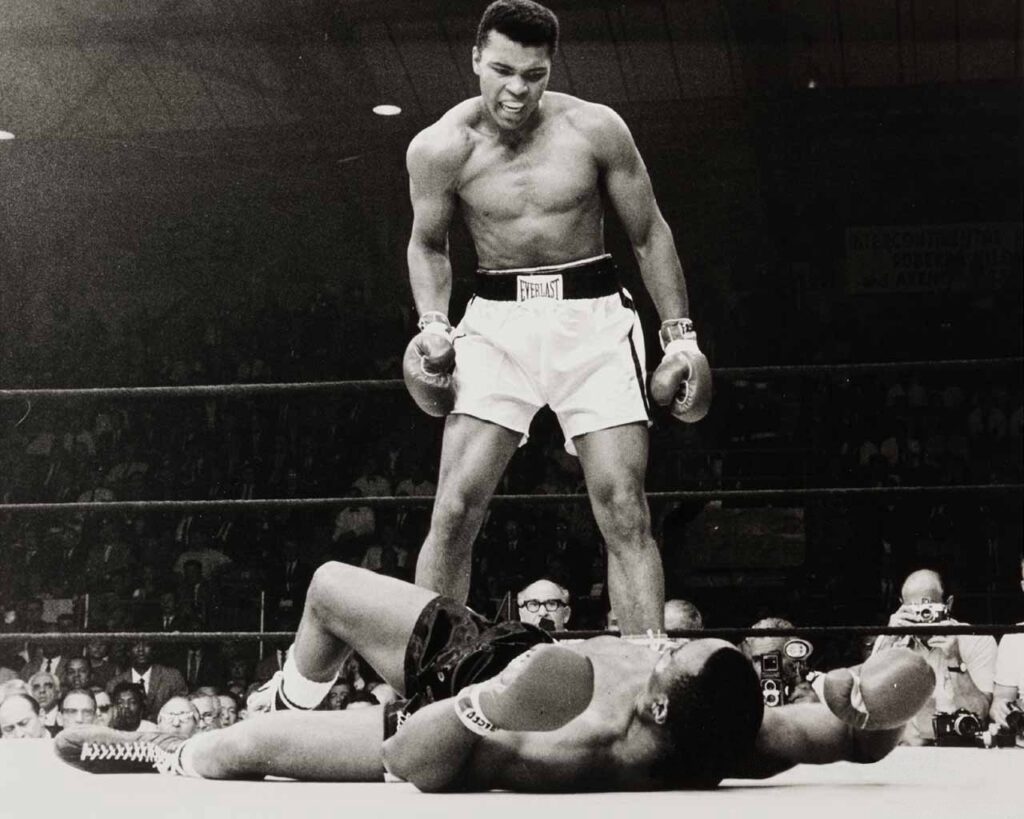

Born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, Cassius Clay began training in boxing at the age of 12. He competed at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, and won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division. After the Olympics, he began his professional career — a career in which he went 56–5 with 37 knockouts over more than two decades. Some of his most memorable wins — against Sonny Liston in 1964, where he first won the heavyweight title; his rubber match against Smokin’ Joe Frazier in 1975’s “Thrilla In Manila”; and his comeback “Rumble In The Jungle” against George Foreman — have been immortalized in modern popular culture.

And, all the while, he never stopped running his talented mouth. If his fists did the talking, his gift of gab was the perfect insult to Ali’s pugilistic injury. He was best known for his sayings like “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” and “I am the Greatest — I said that even before I knew that I was” — a poetic product of his unparalleled in-ring talent.

It was also this gift of gab that he shared with the world at large, beyond the squared circle — one that not only entertained, but made people feel, and made people think, relative to the broad workings of our global society. He spoke out against the Vietnam War, not only by the actions he took — most notably, by refusing army induction in 1967 — but also by succinctly stating his fundamental reason why: “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong.” For those words, and for his actions, three years of his professional life, and his boxing prime, were taken away from him.

His way with words made him such a titan in the realm of media — in an age where wordsmiths had much fewer means and opportunities to be heard — that he was seen as an influence in one of the most creative media in the modern world: Music.

For some, it actually isn’t difficult to see the parallels — after all, Ali’s braggadocian nature, combined with his effortless relationship with the English language and his ruthless barrage of poetic insults, are essentially an early blueprint to modern rap music. In fact, it was a highly-posited theory that “The Greatest” indirectly invented the style of Hip-Hop as it is known today:

Essayist Chuck Klosterman explained this connection between Ali and the DNA of modern hip-hop culture. While the racial undertones were hard to ignore, the “look-at-me” and rebellious attitudes that defined both Ali and the genre of rap (in many of its forms) were undeniably a vital trait for both:

While it’s difficult to prove Ali invented rap music, it’s almost indisputable that he spawned what is now referred to as “the modern athlete,” a term that’s generally used as coded, pejorative language. When someone complains about “the modern athlete,” he or she is usually just saying, “This particular black athlete behaves like a rap star, even though I’ve never actually listened to rap music in my entire life.” These perceived traits include overt self-promotion, indifference toward authority, and confidence that hemorrhages into arrogance.

In fact, one need only listen to his actual spoken-word recordings — in particular, his 1963 release of “I Am The Greatest” — to know that his egotistical language and prose-like deliveries contain the faintest of hints of hip-hop attitude:

But Ali’s influence in music reached well beyond the epoch of hip hop. In his early days as the cocky Cassius Clay, his prowess in the ring inspired many musical tributes in his name — starting with the little-known 1964 tune by The Alcoves, “The Ballad of Cassius Clay”:

The number combines the familiar sound of doo-wop with the mocking poetry Clay used on Sonny Liston before their classic fight — it is practically a perfect marriage between prose and musical style that only a lyrical genius like Ali could inspire.

Ali also inspired tunes based on his life story — as most legendary figures seem to do, in the realm of popular music. For example, American alternative country band Freakwater set, to music, the infamous tale of Ali throwing his Olympic gold medal into the Ohio River.

As the story goes, Ali — whom, at the time, was well-known around the country as American Olympic hero Cassius Clay — wore his gold medal around everywhere he went. But, after a day in which he was denied service at a “Whites-Only” restaurant, and was harassed by a white motorcycle gang, Ali was shown the racist society that simultaneously lauded the accomplishment but dismissed the man who achieved it. In bitterness, he tossed his beloved medal over the Second Street Bridge:

For a much more contemporary example of Ali’s injection into popular culture reflected through music, look no further than The Hours’ 2007 ballad, “Ali In The Jungle”. While the song is more of a motivational vehicle describing how a number of famous historical figures — including Ludwig Von Beethoven and Nelson Mandela — overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles, its central setting is around Ali’s amazing victory over a younger, stronger George Foreman in the Rumble in The Jungle. The song even features real audio from the radio broadcast of the famous 1974 clash:

Tributes to Ali’s lauded face-off against Foreman have been popular through the years, as the well-known reggae ballad “Black Superman” — a 1975 hit by Johnny Wakelin and the Kinshasa Band —as well as “Ali In The Jungle”, have shown:

Ali led an amazing, story-filled life — and Americana, in kind, set much of it to music. As the days and weeks following his death have proven, Ali was the kind of public figure that could only be beloved upon retrospect. While he was a brash, grating champion that rubbed so many the wrong way — either by his mouth, or by his politics — he is remembered the way he should: as a champion for the people, and for the ages.