By Paulo Camacho

Released 30 years ago, Paul Simon’s Graceland album was groundbreaking, controversial, and, some would argue, ahead of its time. Which may be why it is considered one of the greatest albums in American music history.

It was on Thursday, exactly 30 years ago, when the music world was introduced to this:

In case you didn’t know, that was the acclaimed Paul Simon, along with famed SNL alum Chevy Chase, in the music video to one of the former’s greatest solo works, “You Can Call Me Al”. It was a song that, oddly enough, was inspired by a misunderstanding at a party between Simon, his then-wife Peggy Harper, and French composer/conductor Pierre Boulez, who mistakenly referred to the couple as “Al” and “Betty”, respectively, as he departed.

The song’s origin had been a highly contentious point of argument among the music community for the past 30 years. But, surprisingly enough, that isn’t the song’s most interesting bit of trivia. That would go to the song’s bass line — in particular, the song’s instantly recognizable bass solo, and the man that “technically” played it.

Bakithi Kumalo was the man behind the bass — producing a unique sound, with his uncanny ability on a fretless. To say he “technically” played the bass solo on “You Can Call Me Al” needs a bit of explanation: Kumalo produced the first half of the bass solo (which can be heard at 3:44 on the above video). However, Simon loved the solo so much, he decided to artificially extend it — if you listen carefully, you might notice that the entire solo is an audio “mirror image” of itself; that is because Simon extended the solo by playing the tape backwards. Therefore, the solo cannot technically be played properly in a live setting — despite Kumalo’s unmatched talent on the fretless bass.

Kumalo’s unique bass solo is not where his mark on Simon’s music ends. In fact, his presence speaks to a much deeper, more significant meaning behind what would be considered Simon’s greatest, and most controversial, album: 1986’s “Graceland.”

Seen by many as one of the most beloved pop albums of the 20th century, “Graceland” was Paul Simon’s seventh studio album, at a time when his career and his personal life were at a low point. For Simon, it was simultaneously a spiritual revival, both musically and personally, and a lightning rod for controversy — sparking a much-needed debate about the line between honoring an underrepresented population, and unadulterated cultural appropriation.

Simon had recently come off a contentious reunion with former music partner Art Garfunkel, and their latest collaboration — 1983’s Heart and Bones — was a commercial letdown. This was off the heels of his failed second marriage to actress Carrie Fisher. As a result, Simon went through a period of depression — one that was lifted by friend and fellow singer-songwriter Heidi Berg, who loaned him a bootleg cassette tape of South African township music:

It was a happy instrumental music that reminded me of 1950’s rhythm and blues, which I have always loved. By the end of the summer I was scat-singing melodies over the tracks. I thought that the group, whoever it was, would be interesting to record with. And so I went on a search to find out who they were and where they came from.

It was a journey that, unbeknownst to him at the time, would take him all the way to Johannesburg. The music on the bootleg, Simon discovered, was Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits, Volume II — originating from either Ladysmith Black Mambazo or the Boyoyo Boys, both native acts from the politically contentious country of South Africa.

Therein lay the controversy surrounding the album — one, it seems, that still lingers to this day: The country of South Africa was, at the time, in an era of dangerously contentious politics. Under the racist, oppressive regime known as Apartheid, the white minority rule denied many fundamental rights, including citizenship, to its black denizens. As a result, the United Nations issued a variety of bans and sanctions on the country — including U.N. Resolution 35/206, a mandatory call for “all writers, musicians and other personalities to boycott” the nation.

Ultimately, however, Simon would have none of the boycott. He was willing to follow his artistic instincts to work with the South African artists that inspired him to create the album in the first place — the United Nations be damned.

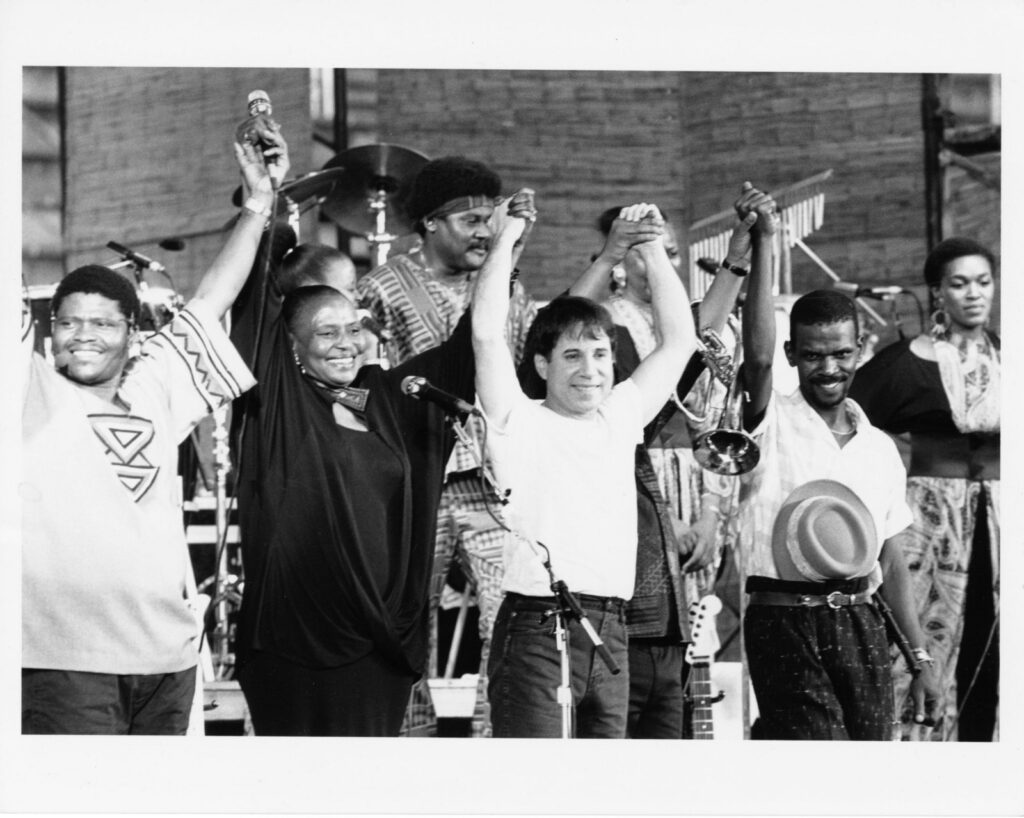

And, thus, in regards to Simon’s decision to record in South Africa, two camps emerged. On the one hand, you had proponents of the decision, who believed that Simon’s collaborations with Soweto-born artists like Mambazo, Kumalo and Chikapa “Ray” Phiri was an altruistic effort to spread their culture to a global audience — something that would not have been possible, otherwise. Some might say that this cultural exposure to the free world was a vehicle to help spread awareness of their country’s despotic plight — which, in turn, might help hasten the end of Apartheid, as they knew it.

On the other hand, many opponents of Simon’s decision did not appreciate the artist essentially thumbing his nose in the face of United Nations sanctions. After all, as with all boycotts, U.N. Resolution 35/206 was meant as a global show of solidarity against the oppressive practices of Apartheid. Simon’s actions displayed a “naive” detriment to that solidarity.

Critics also could not ignore the cultural appropriation — accidental or otherwise — Simon demonstrated by what they deemed as exploitation of South African music. Some went as far as describing Simon’s creative actions as a form of modern colonialism.

However, as the artists themselves would contend, “exploitation” and “colonialism” were inflammatory ways of describing their recording relationship with Simon. In fact, Simon went out of his way to treat his fellow South African musicians as equals. This showed in his paying them $200 an hour for recording sessions; the going Union rate in Johannesburg was $15 a day.

From these recordings, produced a smorgasbord of music unique to the township of Soweto, and a creative blueprint with which Simon could use to create his album. It should be noted that he went to Johannesburg with no songs in mind. As fate would have it, Simon came at the album, creatively, from a reverse perspective: instead of creating the song and having the musicians fill in his vision — a process that Simon was notoriously meticulous with — he would let the musicians dictate the music, to capture the sounds of South Africa, and create songs from there. It was no doubt an artistic renaissance for Simon’s creativity, and his career.

And, despite all of the controversy surrounding the album — including one sparked by, of all things, a Linda Ronstadt cameo — the resulting album, released in August of 1986, became the most successful of Simon’s career, and thrust him back into national relevance. Graceland won Grammys for Best Album in 1987, and for Record of the Year in 1988. It helped popularize African music in the Western world, and, just as important, it brought an amount of personal solace for Simon, in the wake of his depression:

There was the almost mystical affection and strange familiarity I felt when I first heard South African music. Later, there was the visceral thrill of collaborating with South African musicians onstage. Add to this potent mix the new friendships I made with my band mates, and the experience becomes one of the most vital in my life.

You can listen to the entire album below.